Our History

The Clothworkers’ Company boasts a history dating back nearly 500 years, and we value our past and traditions. Although we no longer regulate the finishing of cloth, the craft for which we were originally established, The Company has always been and continues to be a philanthropic membership body today.

To find out more about the key events and personalities that have shaped our long history and the six livery halls that we have called our home, please explore the Timeline at the bottom of this page.

Over the centuries, we have amassed significant collections of works of art, largely through the generosity of past benefactors, and an important archive.

For further information on our collections, archives, and tracing your ancestors please explore the options below.

The Fullers and Shearmen emerge as guilds in the 14th century

In the middle ages, guilds emerged in many towns and cities in England in order to regulate particular crafts. They supervised the training of apprentices and protected consumers and employers by regulating standards of workmanship and prices and preventing unfair competition. They also looked after their members in times of illness, old age or bereavement.

In the City of London, the guilds came to be known as ‘livery companies’, for the distinctive clothing their members wore. The oldest London guild was The Weavers’ Company, which received its Royal Charter in 1155. Over time, groups of craftsmen involved in the different stages of clothmaking formed and later became independent of The Weavers’ Company. Two such groups were the fullers and shearmen, and both were operating as separate guilds by the 14th century. As their numbers and influence grew, both would later acquire halls and become companies in their own right (The Shearmen’s Company issued its first set of ordinances in 1350).

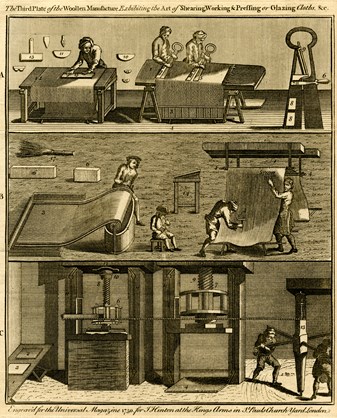

Fullers and shearmen were involved in the final stages of clothmaking, known as ‘finishing’. Finishing cloth traditionally comprised fulling (washing and thickening the cloth in a slurry of water and fullers’ earth or urine), tentering (drying the wet cloth under tension on tenter frames), teaselling (using fullers’ teasels to raise a nap on the surface), and finally shearing the nap to create a fine and even finish. Allied processes included calendaring (pressing), and folding and packing the cloth ready for export or sale.

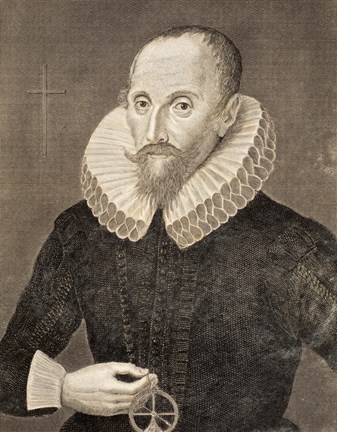

An 18th-century illustration depicting the fulling, teaselling, shearing and planing of cloth

A group of Shearmen acquire the site of the future Clothworkers’ Hall

The Shearmen were one of The Clothworkers’ two predecessor guilds and had emerged as a distinct group of craftsmen in the 14th century. Despite appearing 42nd in a list of City of London guilds in 1376, the Shearmen had not at this time petitioned for a Royal Charter and were thus unable to hold property as a corporate body.

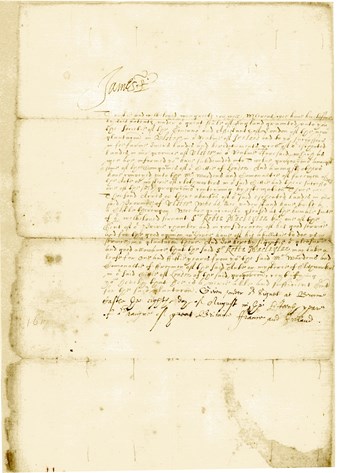

In 1456, premises in Mincing Lane were conveyed by Robert Horn and others to a group of individually named Shearmen, including John Hungerford and William Bette. Shearmen’s Hall was built on the site in 1472. No visual record of its appearance survives; however, it is possible to piece together a picture of its contents and arrangements from an inventory of items owned by the guild, dated 1528.

The main livery hall was arranged with a dais at one end, upon which a long painted table stood. Two further tables ran down either side of the hall, and seating took the form of long benches. The hall also contained a hanging and a beam for five candlesticks. Other rooms included an upper chamber that contained a long trestle table, two benches and a chest; a parlour with a trestle table and a hanging trimmed with red cloth, and a kitchen.

Detail of a conveyance of 15 July 1456 of premises in Mincing Lane - the site of the future Shearmen's Hall, and subsequent Clothworkers' Halls - to a group of Shearmen

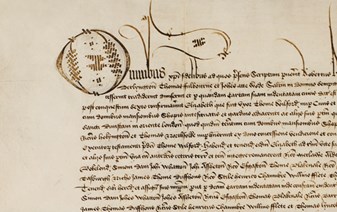

The Fullers’ Company receives a Royal Charter

The Fullers’ Company was incorporated by King Edward VI in 1480. They had originated as a group in The Weavers’ Company and are known to have been operating as a distinct guild during the 14th century. In 1376, they were recorded in 15th place in a list of City of London guilds.

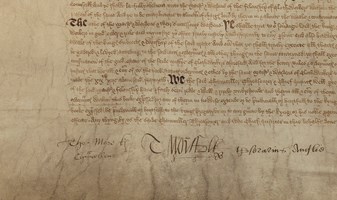

The Charter granted The Fullers’ the right to found a perpetual guild dedicated to the honour of God and the Virgin Mary, in the form of three wardens and a commonalty of Freemen of the Mystery or Art of Fullers. They were permitted to use a common seal, but no provision was made to appoint a Master.

The Fullers’ originally met in Candlewick Ward. By the 1480s, they had moved to Langbourn Ward, north of Fenchurch Street. From 1520 to 1528, they occupied a property in Billiter Lane, next to the original hall of The Ironmongers’ Company. This probably served as their hall until their merger with The Shearmen’s Company.

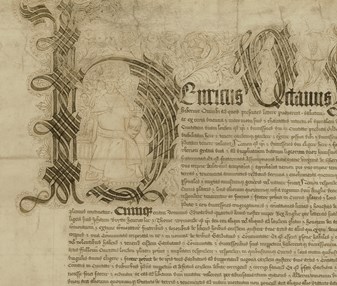

The Charter of The Fullers' Company

The first bequest of property to The Fullers’

By his will of 23 November 1480, William Gardiner, Citizen and Fishmonger, left all his lands, tenements and rents in Haywharf Lane near Thames Street to The Fullers’ Company. Part of the annual rental income was to be channelled towards obits and masses at Austin Friars and the parish church of All Hallows the More, and the remainder was for the Mystery’s own use, provided they kept the land in repair. The property subsequently came into The Clothworkers’ possession when The Fullers’ and Shearmen’s Companies merged in 1528.

Gardiner’s bequest included a set of stairs adjacent to the Common Stairs, giving access onto the Thames, where The Fullers’ – and subsequently The Clothworkers’ – took their ‘bukkes’ (washing tubs) to be cleaned. The Company’s Court Orders contain numerous references to the upkeep of the stairs and fines levied upon members who lent their keys to the stairs to ‘strangers not of The Company’.

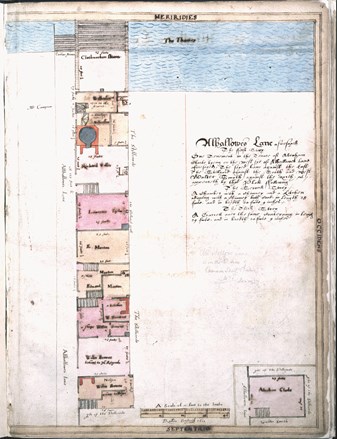

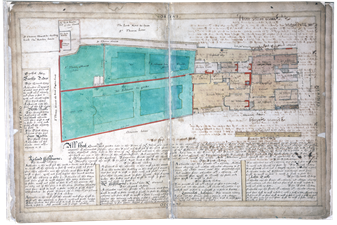

Watercolour plan of the Company's property in Haywharf (formerly All Hallows) Lane bequeathed by William Gardiner, from the Treswell Plan Book, 1612

The Shearmen’s Company receives a Royal Charter

A Royal Charter incorporating The Shearmen’s Company was granted by Henry VII in 1508. It permitted The Shearmen to form a guild or fraternity in honour of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary and defined their rights and privileges. These included the right to hold land in perpetuity, use a common seal and elect out of their own number a Master and two Wardens from year to year.

Their successful petition for a Charter (they had been refused in 1479) marked The Shearmen’s emergence as a powerful body in the City of London hierarchy. In 1515, they were placed 12th in the Order of Precedence settled by Sir William Boteler, then Lord Mayor of London, much to the annoyance of The Dyers’ Company, which was placed in 13th. The Clothworkers’ Company succeeded to The Shearmen’s place in precedence in 1538, when John Tolous, Clothworker, was elected an Alderman.

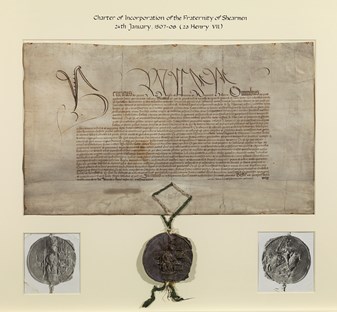

The Charter of The Shearmen's Company

The Clothworkers’ Company receives its first Royal Charter

The Fullers’ and Shearmen’s Companies found that they lacked the power of the older and larger livery companies, and were losing prominent members to those higher in the precedence, such as Alderman William Bayley who translated to The Drapers’ Company in 1514 and become Lord Mayor of London in 1524.

The two guilds decided to unite to strengthen themselves against their rivals. Thwarted by vested cloth interests in the Court of Alderman in 1526, The Fullers’ and Shearmen nevertheless persevered, bypassing the City to petition the crown directly. Some 18 months later, The Clothworkers’ Company was granted its Royal Charter by King Henry VIII on 18 January 1528.

The new company was dedicated to the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary. Among its various provisions, the Charter enabled The Company to elect a Master and four Wardens each year and to hold property, as a corporate entity, in perpetuity. The Charter also granted The Company powers of oversight, search and correction over anyone working woollen cloths and fustians (linen/cotton cloths) in the City of London.

Although founded as a craft organisation, The Clothworkers’ Company soon came to have a number of wealthy merchants amongst its membership. Their interests often differed from those of the artisan craftsmen and a two-tier membership operated within The Company – with the merchants found on the Livery and Court and the craftsman among the Yeomanry of The Company. The Court struggled to maintain a fragile equilibrium between the two groups, and their divergent interests in relation to the export of unfinished cloth would threaten the stability of The Company on several occasions in the future.

Charter of The Clothworkers' Company, granted by King Henry VIII

Clothworkers’ Hall

The newly formed Worshipful Company of Clothworkers took over Shearmen’s Hall in Mincing Lane (built in 1472) and the contents of the nearby Fullers’ Hall were gradually transferred; The Company’s records make reference to ‘conveying the great fire pan from the other Hall’ in 1531 for example. An inventory taken of the contents of the Hall in 1528 hints at the new company’s wealth, beginning with a long list of the silver, jewellery and other ‘stuff of householde’ in their possession. Of these items, only the Common Seal of the Shearmen survives to this day.

The Seal, dated 1509, was adapted for the new company’s use with the crude addition of the words ‘Cloth Workers’ within the frame. It bears The Company’s arms and a depiction of the Blessed Virgin Mary, its patroness, seated under a gothic canopy. It was used to seal all official Company documents for the next 400 years.

The Clothworkers' seal, depicting the Blessed Virgin Mary, the new company's patron

The Company acquires its coat of arms

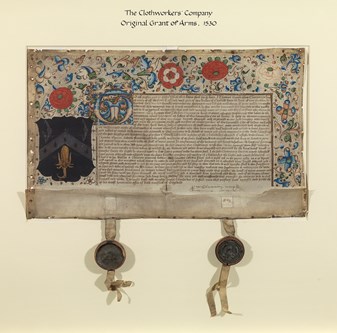

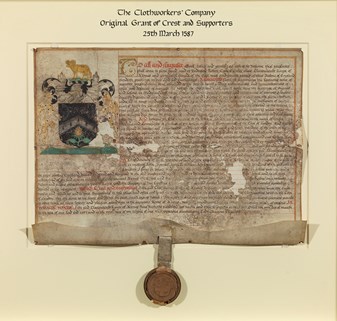

The Clothworkers' arms were granted in 1530 by Thomas Benolt, Clarenceux King of Arms, two years after the foundation of The Company. They may be described as follows: ‘sable a chevron ermine in chief two havettes argent and in base a teasel cob or (a black shield with an ermine fur chevron between two silver habicks above and a golden teasel head beneath)’.

The silver habicks and the golden teasel represent the essential tools of the clothworking craft, the finishing of woven woollen cloth. Habicks were double-edged hooks used to attach lengths of cloth to the shearing table. The dried heads of the fullers’ teasel (dipsacus fullonum) were used to raise the nap of the fabric prior to shearing.

A grant of crest and supporters was received in 1587.

The Company's Grant of Arms

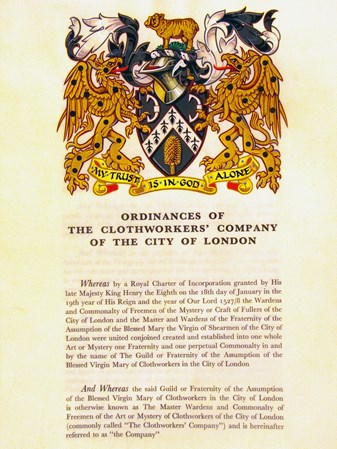

The Clothworkers’ obtain their first set of Ordinances

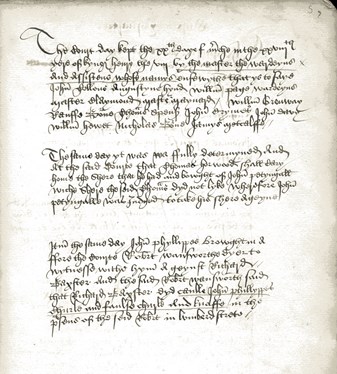

In 1532, The Company’s first Ordinances were ratified. The Ordinances set out in considerable detail how The Company was to be run on a day to day basis and the rules its members were expected to adhere to. These covered attendance at Common Hall after the feast of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary (to whom The Company was dedicated), the composition of the Court, the election of the Master and Wardens and the election of and clothing for the Livery. They also included provisions relating to financial support for those members fallen into poverty (provided they had paid quarterage), attendance at funerals, the presentment of accounts and rules respecting new Householders and the admission of Freemen.

The Clothworkers’ Ordinances are particularly significant as they were signed by Sir Thomas More, then Lord Chancellor of England. Just three years later, More was executed for treason, having refused to swear the Oath of Supremacy.

Detail of The Company's Ordinances, showing the signature of Sir Thomas More, Lord Chancellor

The Company regulates the craft of cloth finishing

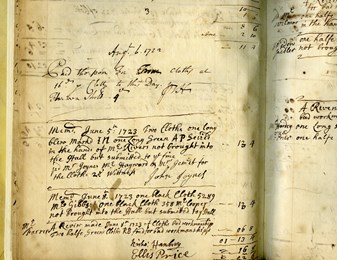

By its Royal Charter, The Company was granted powers to search out and correct bad workmanship of those working (that is, finishing) woollen cloths and fustians in the City of London and The Company’s Court Orders contain numerous references to fines imposed for inferior quality cloths. The very first reference occurs in 1537:

‘The same day yt was fully determyned and at the said Courte that Thomas Horwood shall cary home the shere (shear) that he had brought of John Petyngall wiche shere the said Thomas dyd not lyke wherefore John Petyngall was judged to take his shere ageyne.’

By the custom of London, anyone Free of a company was entitled to ply his trade in the City, irrespective of what that trade might be. As such, many clothworkers were to be found in The Merchants Taylors’ Company, a fact that led to much dispute and strife between the two companies over who should have ultimate control over rights of search and oversight. In 1565, The Clothworkers’ almost ceded their rights to The Merchant Taylors’ – a move that would have required the entire artisan membership of The Clothworkers’ Company to translate to the other livery company – before reconsidering.

An 18th-century book recording fines levied for poor workmanship

The Company swear box

The Company also regulated the behaviour of its members, with fines of 3s 4d imposed on those who swore, made slanderous comments against fellow members or were disobedient. An early reference to the Court’s disciplinary powers also occurs in 1537:

‘The same day John Phyllippes brought in afore the Courte Robert Wansworthe dyer to wytnesse withe hym ageynst Richard Baxster And the seid Robert Wansworthe seid that Robert Baxster dyd caulle John Phyllipes Churle and Faulse Churle and Knaffe (Knave) in the presence of the seid Robert in Lomberd Strete.’

Misdemeanours could be much more serious however. On 19 December 1587, Thomas Kylby was reprimanded for striking Robert Francklyn on the head with a dagger. On 13 June 1592, the Court recorded that Robert Hollande had run away and departed the realm after killing his wife.

The earliest reference to the punishment of members for swearing in the Orders of Court

Margaret, Countess of Kent, The Company’s first female benefactor

Margaret, Countess of Kent the second wife and widow of Richard Gray, 3rd Earl of Kent, died on 5 December 1540. By Deed dated 14 July 1538, and by her Will dated 2 December 1540, she gave to The Company almshouses for seven poor women and a porter at Whitefriars, together with other property in Queenhithe, Fenchurch Street, and elsewhere in the City of London and a sum of £350.

Out of the income of these properties The Company agreed to maintain the almshouses, to pay the porter and to provide £18 annually in support of each of the almswomen.

Having fallen into decay by the 18th century, the almshouses were rebuilt, twice, on land belonging to The Company in Islington. The inhabitants were usually the widows of deceased Freemen.

The Whitefriars almshouses were the first of three almshouses to be administered by The Company. In 1580, The Company took over responsibility for almshouses at Sutton Valence in Kent, established by William Lambe (Master, 1569), and in 1640, John Heath bequeathed £1,500 to The Company to build 10 brick almshouses for poor Clothworkers – duly erected on land also in Islington.

It is believed Margaret bequeathed her properties to The Clothworkers’ as her father, James, had been a member of and benefactor to The Shearmen’s Company.

A 19th-century painting of the Kent Almshouses in their Islington location

The second Clothworkers’ Hall is built

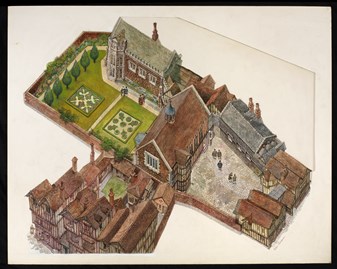

In 1548-9 a new Clothworkers’ Hall was erected by Henry Davyson, bricklayer and John Sampson, carpenter.

The new hall was approached across a courtyard and entered from a screens passage. At one end was a dais, with oriel windows on either side. Some idea of the appearance of this arrangement may be gained from contemporary college halls at Oxford and Cambridge.

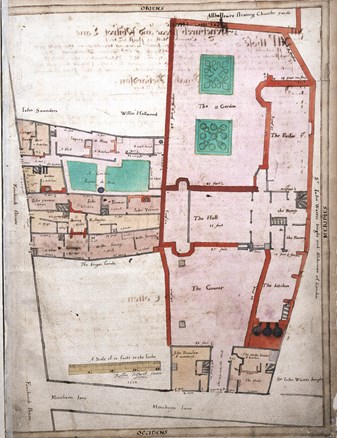

Extant plans in our archive from 1612 show that the Hall and its parlour stood on undercrofts. Above part of the parlour and sharing its oriel was a ladies' chamber. To the west of this lay the ‘Dry Parlour’, with its plate chamber and counting house, and an armoury house over the kitchen and the pastry. There was also a gallery and a further counting house.

An inventory drawn up in 1555 suggests that, at least initially, many of the furnishings were reused from the former hall, for many are described as old and some match the descriptions of pieces in the Shearmen's inventory.

The garden was clearly an important element of the Hall and was newly planted when the Hall was rebuilt. Lists of plants purchased suggest that it was a herb-garden in the form of a knot, planted to be sweet-smelling, with lavender, rosemary, thyme and hyssop, as well as a vine.

Reconstruction of the second Clothworkers' Hall based on the Treswell Plan Book and other recods by Peter Jackson

The Company makes its first educational grant

At a meeting on the 28 April 1551, the Court resolved that ‘where[as] a mocyon was made by my Lord Mayer for the fyndynge of a skoller at the Unyversities, that this house shall yerely paye towards the fyndynge of a skoller five poundes’.

This is the first example of a payment for charitable purposes made by The Company – to a non-Clothworker to fund a scholarship in divinity – and set in train more than four-and-a-half centuries of charitable giving on The Company’s part.

A number of Clothworker benefactors including Barbara Burnell, William Hewett, Edward Pilsworth and John Heath also made provision for the maintenance of divinity scholars in their wills.

Richard Hakluyt, author of The Principal Navigations, Voyages, Traffiques and Discoveries of the English Nation (1589, 1598-1600), was appointed The Company’s scholar at Christ Church Oxford, in 1578.

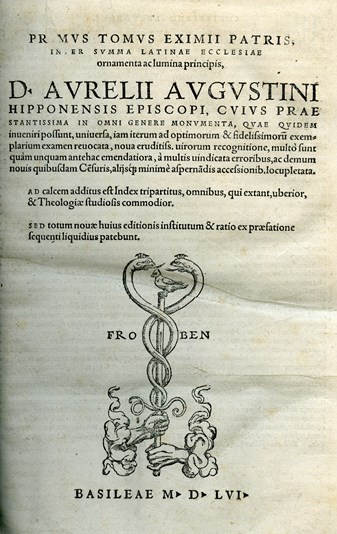

The frontispiece of the Works of St Augustine of Hippo, purchased by The Company for the use of its Scholars in Divinity in 1569

Augustyne Hynde establishes the first loan trust for young Clothworkers

Augustyne Hynde was Master of The Company in 1545 and an Alderman and Sheriff of the City of London in 1550. A wealthy fustian merchant by trade, he imported cloths from the Low Countries and distributed them wholesale nationwide. Hynde had goods valued at £827 in his shops and warehouses at the time of his death and was owed in excess of £6,000 (approx. £1.5million in today’s money) from loans to fellow merchants and credit extended to customers.

In his 1554 will, Hynde left £100 to The Company with which to establish a loan trust. Each year, the sum of £25 was to be lent each to four young men of The Company, for a three-year period, without any interest accruing.

The purpose of the trust was to provide valuable capital that would enable young Freemen to set themselves up as householders (i.e., to establish their own workshops/businesses rather than continuing to work as journeymen for other masters).

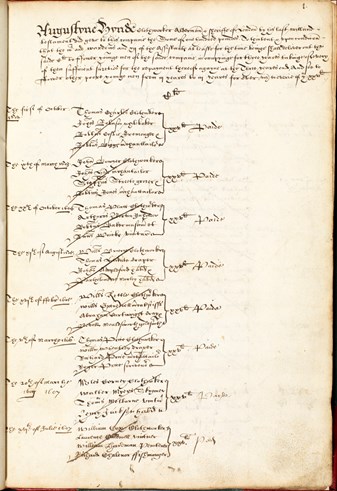

An early form of social investment, loan trusts were a common feature of the charitable provisions of The Company’s benefactors in the 16th and 17th centuries – with Hynde’s trust the first such established – and they were directed towards the benefit of members of The Company, regardless of their actual occupation. The adjacent image of recipients of Hynde’s trust in the early 17th century shows that many members were pursuing crafts other than clothworking.

Recipients of the Hynde loan trust, from an early 17th-century register in the Archive

Thomas Ormeston bequeaths property in Lothbury to The Company

By his will of February 1557, Thomas Ormeston, Master of The Company in the same year, bequeathed his property in Lothbury to The Company, with life interests to his wife and nephew Robert Ormeston. When surveyed in 1612, the property comprised a large house, with garden, entered from Throgmorton Street and three tenements in Copthall Alley.

The property remained in The Company’s possession for several centuries and today forms the north-south spine of The Company’s most important modern estate: supplemented by acquisitions of adjacent plots in the post-war period, Ormeston’s land was redeveloped in the 1970s to form the Angel Court Estate, the income from which provided the original endowment for The Clothworkers’ Foundation (established as The Company’s charitable arm in 1977).

Plan of property in Throgmorton Street bequeathed by Thomas Ormeston, from the Treswell Plan Book, 1612

Sir William Hewett is elected the first Clothworker Lord Mayor

Sir William Hewett (Master, 1543-4) was elected Lord Mayor or London in 1559. He had been elected Alderman of Vintry Ward in 1550 and was committed to Newgate prison for refusing to serve. He served as Sheriff in 1553, and during his term of office was charged with carrying out the execution of Lady Jane Grey. He tried to avoid becoming Lord Mayor, but a small committee prevailed upon him to change his mind.

Hewett’s chief fame today is as the father of Ann Hewett, the girl who fell into the Thames and was rescued by her father’s apprentice, (Sir) Edward Osborne. When Ann grew up, she could have had her pick of suitors, as a wealthy heiress, but Hewett famously pronounced ‘Osborne saved her, let Osborne enjoy her!’ The two later married and their descendants acquired the Dukedom of Leeds.

Hewett was a very wealthy merchant, a member of The Merchant Adventurers’ Company, and a founding member of The Clothworkers’ Company. At his death, he left £15 to The Company towards attendance at his burial, mourning garments and a repast or dinner afterwards. Despite the relatively modest nature of this bequest compared to his overall wealth and other benefactors’ gifts, The Company is delighted to have recently been gifted an original portrait of Hewett, previously on long-term loan to the Museum of London, by Derek Hewett, his descendant.

Portrait of Sir William Hewett c1553, previously attributed to Anthonis Mor

Dame Ann Packington bequeaths lands in Islington

Upon her death in 1563, Dame Ann Packington, the widow of Sir John Packington, Recorder of Worcester left The Company – despite no obvious connection to The Clothworkers’ – one messuage called ‘the Crown’ with lands in Islington. This was the second major bequest by a female benefactor to The Company.

Out of the annual rental income of these properties, certain sums were to be applied towards the poor of the parishes of St Dunstan in the West, St Botolph without Aldersgate and the preaching of two sermons. The residue (approximately one quarter) was to be retained by The Company.

The Company already owned land corporately in Islington. Thus, with the acquisition of the Packington bequest, an extensive estate was formed. It originally comprised farm land, but with the development of the New North Road and the Regents’ Canal in the 19th century, the character of the area changed and rents increased dramatically – as a result, The Company was ordered to divert more of the rental surplus towards charitable ends. By 1927, the estate comprised some 1,052 properties, including houses, factories, shops, public houses and a cinema.

In the 20th century, the Packington Estate was transferred to the City Parochial Foundation and thereafter Islington Council. The Company sold its corporately held property in 1945. But for the survival of St James’ Church and the almshouses The Company had erected there, few relics of the Clothworkers’ long involvement in Islington are evident today.

Eighteenth century plan of The Company's estate in Islington

William Lambe is elected Master of The Company

Born in Sutton Valence, Kent in 1495, William Lambe was described as a gentleman of the Royal Chapel under Henry VIII and may have been a chorister. With his Court connections, Lambe benefitted from the dissolution of the monasteries; in 1543 he was granted the ancient Hermitage or Chapel of St James in the Wall at Monkwell Street by the monarch.

Although married three times, Lambe remained childless. It was perhaps this circumstance that encouraged his charitable activities. He is chiefly remembered for establishing almshouses as Sutton Valence in 1574 and for endowing a grammar school there. However, his philanthropy extended into the field of innovation. In 1577, he financed the construction of a conduit head at Snow Hill, Holborn, to bring fresh spring water to the inhabitants there, almost 40 years before the New River was cut. Lamb’s Conduit Street is so named because of this.

Upon his death in 1580, Lambe left all his property to The Clothworkers’ Company, which in turn took over administration of the Sutton Valence charities for several centuries. Considered to be one of The Company’s greatest benefactors, Lambe continues to be commemorated to this day in an annual service as ‘a person wholly composed of goodness and bounty...as general and discreet a benefactor as any that age produced.’

Portrait of William Lambe by Miss Sprague

Richard Hakluyt is appointed The Company’s scholar in Divinity

Contrary to popular belief, Richard Hakluyt, author, editor, translator and clergyman, was not a member of The Clothworkers’ Company. Born in 1552, he was one of six children of Richard Hakluyt, a member of The Skinners’ Company. He was orphaned at an early age, and his cousin, also Richard Hakluyt, a lawyer at Middle Temple, became his guardian.

Hakluyt was educated at Westminster School and Christ Church, Oxford, taking his BA in 1574 and MA in 1577. In 1578, he became The Clothworkers’ Scholar in Divinity at Christ Church, for which exhibition he received the sum of £1 6s 4d annually. Hakluyt was also paid for providing sermons to The Company; on Lady Day 1581, he preached the annual Lambe’s Sermon at the Church of St. James in the Wall, Monkwell Street.

Hakluyt continued to be funded by The Company until 1587, despite leaving Oxford in 1583 to become the chaplain and secretary to the English Ambassador in Paris. It was at the express request of Lord Burghley, The Lord Treasurer of England that The Company continued to pay his ‘pension’, leading to speculation that Hakluyt was engaged as a spy for the statesman.

Today, Hakluyt is best known for compiling and editing The Principal Navigations, Voyages and Discoveries of the English Nation, considered to be the most important collection of travel writing in the early modern period. It includes the first detailed account of St Francis Drake’s circumnavigation of the world amongst other accounts that only survive today in the printing by Hakluyt.

Richard Hakluyt depicted in a stained glass window in Bristol Cathedral (By kind permission of the Chapter of Bristol Cathedral)

Grant of crest and supporters to The Clothworkers’ Company

The Company’s crest and supporters were granted in 1587 by Robert Cooke, Clarenceux King of Arms. They may be described as follows: ‘crest – on a wreath argent and sable a mount vert, thereon a ram statant or; mantling – sable doubled argent; supporters – on either side a griffin or pellety (the shield is surmounted by a helmet topped with a golden ram standing on a green hillock with a base of black and silver and draped with black mantling lined with silver. It is supported on either side by golden griffins with spots)’.

The golden ram represents the idea of sheep supplying wool, traditionally considered the ultimate source of The Company’s wealth. It may also echo the Golden Fleece of Greek mythology. It may also be a mild pun on the word 'ram' and the French word 'rame', meaning a clothworker's tenter frame. The mantling is in The Company's heraldic colours, black and white (or silver). The spotted griffins, half eagle and half lion, are associated with the guardianship of treasure and the enactment of good deeds.

The Company's motto, 'My Trust is in God Alone' was adopted at an uncertain, though early, date. However, it does not appear on either grant of arms. It is apparently not taken from the Bible, but expresses a common sentiment at the time of adoption (for example the anthem 'O Lord, in Thee is all my trust', ascribed to Thomas Tallis, popular in the 16th and 17th centuries).

Grant of Crest and Supporters

King James I of England and VI of Scotland becomes a Clothworker

Born in 1566, the son of Mary Queen of Scots was crowned King of Scotland the year following the abdication of his mother. He succeeded to the English throne in 1603. When King James first came to dine in the City of London, he dined in the home of a Clothworker (John Watts, Master 1594). He was invited to join The Company, to which he readily agreed, being admitted with a handshake in June 1607, although the legality of the mode of admission is questionable. King James was The Company’s first royal Freeman. At his admission he reputedly toasted The Company with the following words: ‘God bless all good Clothworkers, and God bless all good cloth wearers!’

King James also made a gift of two brace of bucks to The Company each year on the anniversary of the election of the Master and Wardens. Sadly, the practice fell into abeyance, although an attempt was made, unsuccessfully, to revive it in 1870.

Engraved illustration of King James I of England, the first Royal Clothworker

The Clothworkers’ Company invests in the Virginia Company

On 6 April 1609, all members of The Company was summoned to Clothworkers’ Hall to hear a precept by the Lord Mayor of London and a letter from the Council of the Virginia Plantation read. Both were written to solicit support from members in the establishment of settlements on the East Coast of America, but ‘they thereupon did not show any forwardness to that Adventure.’ Members were given two days to think the matter through, but interest was disappointing. As a result, The Company ventured to supplement the low level of individual contributions to make up a balance of £100 in total.

Fortunately, other supporters were forthcoming. The second Charter of The Virginia Company of 23 May 1609 listed a number of Clothworkers among its investors, including Sir John Watts and John Eldred. Eldred was a very successful merchant and a member of the Levant, Muscovy and East India Companies and would have been keen to establish new markets overseas for the cloth he exported.

Despite the optimism of some – Jeremy Norcross, Clothworker was voted £10 by the Court towards his intended journey to New England – the colony did not prosper. Many of the original settlers perished due to starvation in the years 1609-1610, ‘the starving time’, and it became clear that the sponsors had underestimated the capital required to maintain the colony. Lotteries were established to raise funds, and The Company ventured a further £50 when a third Charter was granted. Although it is believed that some colonists prospered trading in Virginian tobacco, The Clothworkers’ records say nothing regarding any returns on investments.

Following the Jamestown Massacre, the Virginia Company was dissolved and Virginia re-established as a royal colony with a governor subject to King James I.

Portrait of John Eldred, Clothworker and merchant, a prominent investor in the Virginia Company

The Company invests in the Irish Plantation

In January 1609, a comprehensive plan was drawn up for the colonisation of Ulster. King James intended that loyal planters should settle on lands confiscated from the Irish and thus help bring stability to the province after many decades of resistance to the imposition of English law and English rule. The City livery companies were integral to his plans and a precept was issued in order to solicit financial backing from them. The Clothworkers’ decided to have no part in the plantation – the request for funds coming so soon after investment in the Virginia Company – however, fines were levied upon individual members, many of whom struggled to meet their instalments.

As the process of gathering funds proved protracted, the Crown instead decided that the companies should accept a proportionate share of the Ulster lands to ‘to build and plant at [their] pleasure, costs and charges’. The Clothworkers’ proportion was shared with The Merchant Taylors’, Butchers’, Bowyers’, Fletchers’, Brownbakers’ and Upholders’ Companies, although The Butchers’ released their rights in the Estate in favour of The Clothworkers’ in 1675.

The Clothworkers’ Company was perhaps one of the most reluctant companies to become involved in the Plantation and distanced itself from its development. From the start, The Company’s policy was to grant long head leases of its proportion, which lay on the left side of the River Bann, opposite Coleraine.

By the 19th century, conditions on the Estate were poor; when the head lease fell in, The Company took direct control and set about making improvements. The Estate was surveyed by Edward Driver (Master Excused Service 1839 and member of the Driver property surveying dynasty), and his recommendations – including land drainage, embankment of the Bann and the development of Waterside – were implemented. New roads, churches and houses were built, trees planted, bog lands drained and land enclosed. A plot of land was also granted for the site of the Coleraine Academical Institution, inaugurated in July 1860, and 200 guineas towards the building. A Clothworkers’ prize at the school, initiated to be awarded to the best performing student each year, continues to this day.

In 1871, The Company sold its estate to Sir Hervey H. Bruce M.P.

Letter signed by James I permitting The Company to lease their Irish Estate to Sir Robert Macleylan in 1617

The Company commissions a survey of its estates

On 24 September 1611, Ralph Treswell, a member of The Painter-Stainers’ Company and a surveyor by trade, was asked by The Clothworkers’ Company to prepare a ‘plott exactly drawen & made of all the landes and Tenements belonging to this Company in their severall places and scituat[i]ons at the chardges of this house’.

The resulting plan book was presented to The Company on the 3 September 1612 and comprises watercolour ground floor plans of The Company’s properties within the City of London and beyond in Islington, Warley, Upminster and Kent. The plans record the exact dimensions of every room in every house The Company owned and indicate the presence and precise location of stairs, windows, doorways, passageways, courtyards, gardens, hearths and privies. Written descriptions of subsequent storeys in each property accompany the plans, which also name individual tenants.

The Plan Book provides us with our only original visual representation of Clothworkers’ Hall before the 19th century and represents an important source for cartographical, genealogical and metropolitan history.

Despite his endeavours, The Company paid Treswell £35 for his services – £50 had been requested – and additionally asked him to survey their lands in Sutton Valence, Kent and Essex.

Watercolour plan of Clothworkers' Hall from the Treswell Plan Book, 1612

Artisan Clothworkers and the Cockayne cloth project

In 1613, a group of artisan Clothworkers, with the support of Alderman Cockayne, petitioned Parliament to prevent the export of unfinished cloths from the Kingdom. Cloth was England’s largest export, and the livelihoods of many London craftsmen were threatened by overseas competition – thus a preference for English cloths to be exported unfinished.

The proposal put The Clothworkers’ Company in a difficult position. Whilst the petition – made without the Court’s consent – aimed to improve the livelihoods of its craftsmen, many of the Assistants were themselves merchants and members of The Merchant Adventurers’ Company and felt their interests threatened by such a move. It was not the first time that the interests of The Company’s members had diverged; in 1565, artisan Clothworkers successfully petitioned Parliament to alter The Merchant Adventurers’ charter, winning the important concession that 1 in every 10 cloths exported should be finished.

On this occasion, the artisans were again successful, and Alderman Cockayne was granted a monopoly on the export of dressed cloths under a new company – the New Merchant Adventurers’. However, the Dutch boycotted British cloth, forcing prices to drop. British merchants also refused to purchase foreign cloth for finishing and export, thus stymieing the cycle of trade. Cockayne’s cloth project collapsed, and The Merchant Adventurers’ had their rights reinstated, leading to widespread unemployment and poverty amongst craftsmen.

The Great Fire of London and the Industrial Revolution – along with the migration of clothmaking and finishing out of London – are usually considered to be the primary factors in The Company’s divorce from its craft. However, ongoing tensions between the merchant and artisan Clothworkers, which continued to flare until the 1740s, cannot but have harmed the London clothworking industry. By the 18th century, The Company’s regulation of its craft finally diminished with the last searches for bad workmanship taking place in 1749.

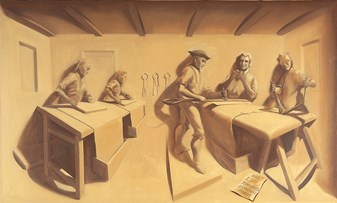

A trompe l'oeil panel by John O'Connor depicting the sheaing and planing of cloth

The Company acquires its own barge

Travelling by river was the most efficient form of transportation to and from the City, Westminster and the north and south banks of the Thames in the days before an efficient road network. The Company often had to hire a barge, sometimes sharing with The Skinners’ Company, for use when the Lord Mayor travelled to Westminster. Bedecked in silk banners and streamers, the barge would have carried members of the Livery in addition to trumpeters as it processed along the river.

It appears from references in The Company’s Court Orders that there were not always sufficient barges available to lease; those hired could become very crowded and wherries also had to be used to carry the overflow of passengers. In 1623, William Foster, a Clothworker lighterman, offered to build a barge for The Company’s sole use. The new barge was capable of carrying 60 men, and Foster undertook to have the barge, rowers and steersman ready for use at a day’s notice.

The new barge was moored at a bargehouse in Vauxhall, and quarters were provided there for The Company’s bargemaster. The bargemaster was required to wear a livery (coat and breeches) of scarlet cloth and a gold-laced hat. In 1787, a silver gilt badge was struck for him by Henry Green, a Clothworker silversmith.

Despite the stately pace of the river passage, The Company’s fine rococo-style silver-gilt mace by Samuel Courtauld was accidentally dropped into the Thames during the Mayoral procession in 1803. Account books in the Archive reveal that the princely sum of £2 3s was paid to the unfortunate who waded into the filthy waters to, successfully, retrieve it.

The Barge-Master's badge by Henry Green

The third Clothworkers’ Hall is built

The second Clothworkers’ Hall had been enlarged and beautified following the admission of King James I to The Company’s Freedom; however, by 1633, the walls were found to be ‘much defective and cracked, the windows unfashionable and the whole frame uncomely and without ornament’. It was decided to rebuild entirely, and enlarge, and the third Clothworkers’ Hall was completed within a year.

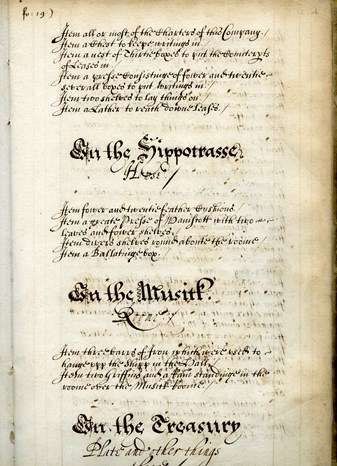

No visual record of its appearance survives; however, we know that it was entered from Mincing Lane and a courtyard was crossed to reach the Livery Hall, like the previous Hall. An inventory of contents made in 1653 shows that The Company’s new home included a number of new rooms for entertaining in such as the ‘Hippocras’ House’ (where the spiced wine was taken) and a music room. Samuel Pepys recorded a visit to the Hall in his diary on 28 June 1660: ‘Our entertainment very good. A brave hall. Good company and very good Musique.’

A 17th-century inventory of Clothworkers' Hall, listing the contents of the Hippocras House and the Music Room

Financial troubles and the Civil War

The livery companies were often viewed as a source of ready cash by the monarchy, and during the political troubles of the 17th century they received many demands for money. Unable to meet the King’s precepts, The Company was forced to borrow from individual members. When Civil War erupted in 1642, further demands arrived, now from Parliament and the City. By September 1643 the Court decided:

‘Taking into their sad and serious considerations the many great pressing and urgent occasions which they have for money as well as for the payment of their debts as otherwise and considering the danger this City is in by reason of the great distractions and Civil Wars of this Kingdom have thought fit and ordered that the stock of Plate which The Company hath shall be sold at the best rate that will be given for the same.’

Approximately two-thirds of The Company’s collection was sold, to raise a total of £520 1s 8d. Of the pieces saved, only the rosewater dishes given by John Burnell and Joseph Jackson survive to this day.

During the Civil Wars, The Clothworkers sided with Parliament, as did the City – indeed, the Master of The Company in 1652-3 was Alderman Sir John Ireton, whose brother, Henry Ireton, had signed King Charles’ death warrant. However, The Company was quick to shift allegiances when required. At the restoration of Charles II in 1660, they went to great effort to welcome the King into the City with suitable splendour. The Company’s trumpeter and six handsome, tall and able men were lent to the Guildhall to serve the meat; £165 was given towards the cost of the banquet, and members lined the streets in their finest attire with cloths, banners, streamers and ornaments resplendent around them.

Two pieces of The Company's surviving plate after the 1643 sale - rosewater dishes given by John Burnell and Joseph Jackson, past Master

The Great Fire of London destroys Clothworkers’ Hall

The Great Fire of London broke out in Pudding Lane on the night of 1 September 1666. It very soon reached the Steelyard, causing chaos at Clothworkers’ stairs at the bottom of Haywharf Lane as residents threw themselves and their belongings into the Thames to escape the flames. The fire also spread eastwards, reaching Clothworkers’ Hall, of which Pepys remarked ‘But strange it was to see Cloathworkers-Hall on fire these three days and nights in one body of Flame’.

The building was not instantly consumed, on account of its brick construction, and the fourth Clothworkers’ Hall seems to have been in part a re-facing of the third’s fire-damaged walls. During the fire, The Company’s Archive was evacuated to Drury Lane, and the damaged livery hall was guarded by watchmen and two (and later three) dogs to keep the site secure – there being a proliferation of lead thieves in the City. In the fire’s wake, The Company held its meetings at Lambe’s Chapel in Monkwell Street before Dennis Gawden (Master, 1667) offered to rebuild the Hall at his own cost – to be repaid by The Company later, when it was in a better position to do so.

By 1668, the new Hall was complete and was described by Maitland as:

‘a noble rich building. The Hall is... a lofty Room, adorned with wainscot to the Ceiling where is curious Fret-wrot. The Screen at the South End if of Oak adorned with four Pilasters, their Entablature and Compass Pediment is of the Corinthian Order enriched with their Arms and Palm Branches. The West end is adorned with the Figures of King James I and King Charles I, richly carved as big as the Life in their Robes with Regalia, all gilt with Gold, where is a spacious Window of stained Glass.’

Entries in the Account books recording payments for evacuating The Company's Archive to Drury Lane and watching over the Hall after the Great Fire

Samuel Pepys is elected Master of The Clothworkers’ Company

On 7 August 1677, the Honourable Samuel Pepys Esquire was chosen Master of The Clothworkers’ Company.

Pepys was a well-connected and very senior naval civil servant, resident in nearby Seething Lane, but he was not a Freemen or indeed Liveryman of The Company. It is believed that The Clothworkers’ took the extraordinary decision to welcome him into the Master’s chair in order to cultivate friendships at Court, so soon after the Civil Wars when The Company and City had turned out for the Parliamentarian forces.

Pepys was in effect a token Master, only making five appearances at Court during his year of office. In spite of this, he is considered our most famous Past Master on account of his diaries (which sadly terminate before his year of office) and for his munificent gift of three pieces of plate to The Company, which are considered our finest treasures. They comprise a rosewater dish, ewer and a silver-gilt pierced and engraved cage work loving cup – the latter was considered by Pevsner to be ‘perhaps the most magnificent cup in the City.’

Portrait of Samuel Pepys by Riley

Sir Robert Beachcroft becomes Lord Mayor of London

On 30 September 1668, Robert Beachcroft, the son of Daniel (yeoman of Derby), was apprenticed to Thomas Palfreyman, Clothworker, for seven years. He became Free of The Company on 5 October 1675.

Beachcroft was a merchant by trade, deriving great wealth from the export of cloth. In 1700, he became Master of The Company, and in 1711 he took up the mayoralty of the City of London.

City Poet Elkanah Settle presented Beachcroft with a congratulatory address on his inauguration, in which he cited the importance of the cloth trade and The Clothworkers’ Company:

Augusta Triumphans

When up to her Great SONS of INDUSTRY,

The fair AUGUSTA lifts her well-pleas’d Eye;

And her Rang’d CITY WORTHIES on each side,

Do’s into Twelve Chief COMPANIES divide:

Oh! Why, in these Distinctions Classes Plac’d,

The MERCERS First, and CLOTHWORKERS the Last?

All a mistake! Ill marshall’d Herauldry!

Look up to their Great LABOURS, and there see

Their sweating Brows Unequall’d GLORIES shine.

Who but thy CLOTHWORKERS, proud ALBION, layd

Ev’n thy Foundation of COMMERCE and TRADE?

Beachcroft died, childless, in 1721. He made a number of liberal bequests, including to St Thomas’ Hospital, and was buried at Low Leyton in Essex, where a monument was erected to his memory. Our first lady Master, Dr Carolyn Boulter DL, is a descendant of Sir Robert and generously presented this full-length portrait of her ancestor by Richard van Bleeck as her Master’s gift in 2018.

Portrait of Sir Robert Beachcroft attributed to Richard Van Bleeck

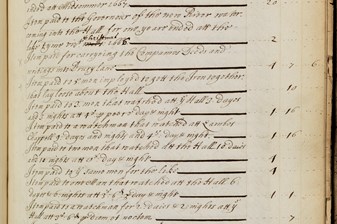

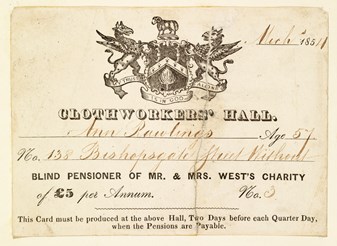

(1713 - 1724) The John and Frances West charitable trusts are established

John West, the son of Simon West, Citizen and Stationer of London was born in 1641. He was made Free of The Company in 1666 and became an eminent scrivener by profession. He became Master of The Company in 1707.

West had held a retainer as a scrivener for Samuel Pepys, and was one of the four witnesses to the latter’s will, for which duty he received a mourning ring from the diarist. However, he and his wife Frances, are principally remembered for the generosity of their gifts for charitable purposes, made during their lifetimes and following their deaths.

The Wests established a number of charitable trusts to which The Company was appointed, or subsequently became, the trustee. Artisan Clothworkers, apprentices and Blue Coat Boys at Reading were some of the beneficiaries of these, but by far the most important aspect of their benevolence was for the notable assistance they provided towards people with blindness. The trusts provided pensions for economically disadvantaged blind persons, with particular preference for the Wests’ own kin.

Following later administrative reforms, these trusts were consolidated and came to be known as the West Relations Trust. Trusteeship of this has now passed to Christ’s Hospital, which also manages other charities by which the kindred of the Wests may benefit.

The West Trusts signalled the start of The Clothworkers’ centuries-long association with assistance for people with blindness. The Company subsequently became trustees of other charities supporting partially sighted or blind people, such as the Blind Man’s Friend Charity and the Society for Granting Annuities to the Poor Adult Blind, as well as long-held connections with the Royal National Institute for the Blind and the Metropolitan Society for the Blind. Visual impairment is now one of the core areas in which the grant-making of The Clothworkers’ Foundation, The Company’s charitable arm, is directed today.

Pension card of Ann Rawlings, a blind pensioner of Mr and Mrs West's Charity

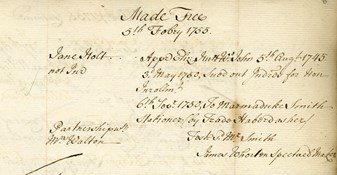

Louisa Bonwick, the last female apprentice

On 4 November 1793, Louisa Bonwick was apprenticed to Robert Ryder, Clothworker and by trade a calico glazer. She was the last of a total of 144 girls to be apprenticed through The Company throughout its history (recorded in our registers of apprentices, which survive from 1606).

Although female apprenticeships represent only a small proportion of the total number of apprenticeships in The Company’s history, it is important to acknowledge that women were not excluded from occupational training, however unclear The Company’s Charters and Ordinances might be regarding the ‘sustren of the mistery’ and in spite of a prevailing belief that there was no place for women in guilds and livery companies.

A majority of these female apprentices received training to enter the textile trades, in particular millinery. Millinery was considered a reputable profession for girls of middling and genteel origins in the 18th century, and apprenticeships in this areas often commanded much higher premiums than those trades in which boys were trained.

Although very few women went on to take up their Freedom of The Company after the completion of their indentures, the 18th and 19th centuries witnessed a significant increase in the number of women achieving the Freedom of The Clothworkers’ Company by patrimony. Women are also recorded as mistresses in the training of both female and male apprentices in nearly 1,000 apprenticeship records between the years 1606-1800, suggesting that wives and, in particular, widows of Clothworkers were economically active, taking advantage of their husbands’ ‘Free’ status to run businesses with or independently of their husbands, although the full extent of their activities otherwise escape the written record.

Male apprenticeships through The Company did not cease until 1908.

Freedom record of Jane Holt, who established a successful millinery business in Lombard Street

Thomas Massa Alsager is elected Master

With the decline of the London clothworking industry in the previous century, as a result of the Great Fire and the Industrial Revolution, The Company entered a period of relative stagnation, struggling to find a new purpose. Its affairs were transformed upon the election of Thomas Massa Alsager as Master in 1836.

Born in 1779, Alsager was a successful businessman. He was one of the founders of The Times newspaper and the originator of its City page. He also had a keen interest in music – organising a series of recitals that led to the foundation of the Beethoven Quartet Society in 1845.

During his year as Master, Alsager discovered that The Company’s financial affairs had been allowed to fall into a perilous state. Too much responsibility had been allowed to devolve upon the Clerk unchecked, and, as a result, thorough reform was required. Alsager overhauled The Company’s administration, implementing new accounting procedures and introducing a system of standing committees with clear reporting structures for the first time. In so doing, he transformed The Company into a modern-looking financial corporation, enabling it to enter a Victorian ‘golden age’ and to become more heavily involved in charitable work. For this reason, he is considered The Company’s most important Master.

Portrait of Thomas Massa Alsager standing beside the Master's chair with the books of Orders of Court beside him (by G.P. Harding)

Alderman Sir John Musgrove elected the 24th Clothworker Lord Mayor

Sir John Musgrove was Lord Mayor of London for the in 1850, the year of the Great Exhibition (in which The Company was an enthusiastic promoter).

Musgrove entertained many distinguished personages at Clothworkers’ Hall during his Mayoralty, but he is principally remembered for reintroducing pageants into the Lord Mayor’s show. His parade included horses of Europe, deer of America, camels of Asia, and an elephant of Africa to represent the four corners of the globe. ‘The exquisite scent of the latter rendered it impossible that it could have been introduced earlier in the procession’, remarked Charles Dickens’ fictional character, Mr Booley, of the spectacle.

Punch mocked Musgrove’s ostentation: ‘Parturiunt montes, nascitur ridiculus Mus(grove)’, translated as ‘The mountains labour and bring forth a ridiculous mouse/Musgrove’.

Illustration of Sir John Musgrove's mayoral parade

St Thomas Eve ‘lunch’ tradition begins

St Thomas’ Eve (20 December) was originally the day on which the distribution of gifts from The Company’s Trust funds was made to poor Clothworkers, in adherence of the wishes of its past benefactors and a British tradition of benevolence on this date.

It was customary in many parts of the country to ‘go a Thomasing’ on St Thomas’ Day, when children of the poor went to the local manor house to receive gifts of food or money for the Christmas season. In the Black Country it was known as ‘Gooding Day’ and in Ampthill (Bedfordshire), where a parish dole of bread was distributed, it was known as ‘Tommy Loaf Day’.

Traditionally, poor members of The Company would come to Clothworkers’ Hall to receive alms distributed by the Beadle from The Company’s various charitable trusts on this date. From 1858, The Company additionally ordered that ‘Applicants for Relief on St Thomas’s Eve should [also] have some refreshment afforded them. The Committee recommended that the Beadle be instructed to provide cold meat, bread and beer on the occasion.’

The St Thomas Eve lunch tradition was thus born, and has continued for more than 150 years, but for wartime interruptions and the introduction of more modern menu. Today, the practice of distributing aid to members at the lunch has declined, and the event has evolved into an event for members of the Freedom and staff, and all attendees receive a gift of oranges to take away (the latter custom is of uncertain origin, but continues to be faithfully adhered to).

19th-century drawing of members of The Company at the St Thomas Eve lunch at Clothworkers' Hall

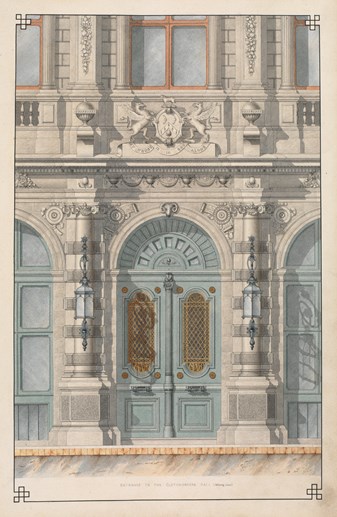

The fifth Clothworkers’ Hall opens for business

In 1855, Samuel Angell, The Company's surveyor, wrote a report on the state of Clothworkers' Hall. Nearly 200 years old, the structure was deemed to be unsound and incommodious, and he recommended that the whole be pulled down and rebuilt.

The hall was demolished in 1856, and a new building erected according to Angell's designs. Like many contemporary buildings in the City, it was Italian Renaissance in style. The Times dubbed it 'one of the finest of which the City can boast'.

The main entrance remained on Mincing Lane, behind an imposing facade – depicted in this watercolour from c 1872 – with the livery hall was on the first floor, still oriented North-South. However, the building now took up most of the site and formed a single, though picturesque, block rather than being arranged around internal courtyards.

The wealth of The Company was reflected in the sumptuous interiors, with ornate polychromed and gilded plasterwork and lavish use of polished granite and marble. The new hall was opened by His Royal Highness Prince Albert, The Prince Consort, who was presented with the Honorary Livery of The Company on the same day.

Watercolour of the entrance to the fifth Clothworkers' Hall on Mincing Lane

St Olave’s becomes The Company’s guild church

Historically, there was a strong religious element in the guilds, with each adopting a patron saint and affiliating themselves with a local monastery or church. St Dunstan-in-the-East was the ancient parish church of Clothworkers’ Hall; however, many of The Company’s religious ceremonies took place at the Chapel of St James in the Wall, Monkwell Street, granted to The Company by William Lambe in 1568. It was here, for example, that The Company met for Court meetings following the Great Fire in 1666.

The Church of St Olave in Hart Street became more closely associated with The Company through the parochial reorganisation of the 1870s that united its parish with that of All Hallows Staining, whose tower and churchyard became the property of The Company at this time. Following the closure of Lambe’s Chapel in 1872, St Olave’s came to be used for Company sermons, and, since the early 20th century, The Company’s chaplain has also been the rector of St Olave’s.

It is fitting for St Olave’s to be The Company’s guild church, as it is the church in which Samuel Pepys – The Company’s most famous Master – worshipped and was buried. It is now the setting for The Company’s annual Election and St Thomas’ Eve services, and we make annual grants to the Friends of St Olave’s towards the maintenance of the fabric of this historic church.

St Olave's in Hart Street

First steps in technical education

The Company first considered lending its support to the movement for technical education in textiles and the cloth trade in 1872.

Initially, the Court decided to award medals for textiles at the International Exhibitions and commissioned designs from George Adams for medals to be presented at Vienna in 1873. However, attention soon turned to the desirability of encouraging the movement ‘at the principal centres of that industry’ in this country, and, on 8 May 1873, The Company hosted a conference of Yorkshire Mayors and Chairmen of Commerce to discuss the issue at Clothworkers’ Hall. The conference was addressed by Obadiah Nussey, a prominent mill owner and former Mayor of Leeds. He said that it was essential to establish schools like those in Germany, France and Belgium for 'practical trade instruction' so that Britain would not lose its place in the world of manufacturing.

The Company was receptive to his appeal; £10,000 was granted towards a Department of Textiles Industries at the new Yorkshire College of Science in Leeds and a second department of Dyeing and Tinctorial Chemistry subsequently followed, similarly funded by The Clothworkers’.

The Company also supported similar ventures at Bristol, Bradford and Huddersfield Along with The Drapers’ Company, The Clothworkers’ Company was a pivotal mover in the establishment of The City and Guilds of London Institute in 1876.

Despite changes of nomenclature, and the granting of University status in 1904, The Company’s support of its two departments at Leeds (the School of Design and the Department of Colour Science today) has continued ever since, principally through the funding of equipment, bursaries and annual grants. However, assistance has also been given towards wider university projects including residential accommodation for students, a concert hall and refurbishment of Clothworkers’ Court and the Great Hall as well as the establishment of the Clothworkers’ Innovation Fund.

Most recently, Clothworkers’ gave a £1.7m anchor donation to create the Clothworkers’ Centre for Textiles Material Innovation for Healthcare (CCTMIH), in recognition of the important uses of textile materials in healthcare devices being developed for the detection, treatment and prevention of diseases and illnesses.

Plaster maquette of a medal for textiles, designed by G.G. Adams, c1873

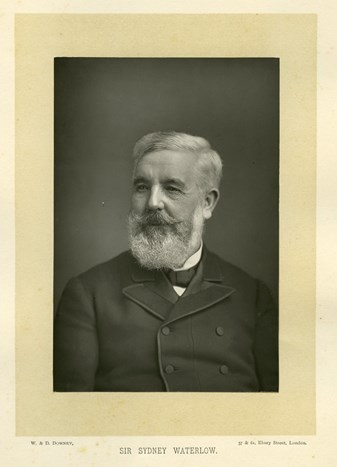

Sir Sydney Waterlow, Lord Mayor of London joins The Clothworkers’ Company

Sydney Hedley Waterlow was the 26th Clothworker Lord Mayor. Waterlow was born in 1822, the son of a member of The Stationers’ Company. He was brought up by his grandmother in Mile End before being apprenticed to his uncle, a member of The Stationers’ Company and printer by trade from the age of 14. After taking up his Freedom of The Stationers’ in 1843, Waterlow joined the family business in Birchin Lane, proving pivotal in the establishment of what became its highly profitable printing arm. As a result, he was well known in the City and first held civic office as Common Councillor in 1857. In 1863, he became Alderman of Langbourn Ward, and, in 1872, Master of The Stationers’ Company and Lord Mayor of London.

Waterlow was a great philanthropist, keenly interested in the improvement of housing for the labouring classes. In 1862, he built, at his own cost, four blocks of dwellings in Mark Street, Finsbury, and the following year established the Industrial Dwellings Company, one of the two main providers of working-class housing in later Victorian London. In 1882, he gave his home, Lauderdale House in Highgate, to St Bartholomew’s Hospital for use as a convalescent home and later famously donated the 29-acre estate surrounding it to the public as a ‘garden for the gardenless’.

As The Company’s charitable work burgeoned in the Victorian era, it was fitting that The Company should welcome a number of great philanthropists into its wings. George Peabody was given the Honorary Freedom of The Company in 1862 in recognition of his gift of £150,000 to the poor of the City, and, in the same month as Waterlow, the Right Honourable Angela Burdett-Coutts was also awarded the Freedom of The Company in July 1873. Sir Edward Cecil Guinness, the 1st Lord Iveagh, was similarly honoured in 1890.

Although Waterlow did not become a Master of The Company, he was nonetheless an important figure in its 19th-century resurgence. It was he that proposed a motion to the Court to support the establishment of the City and Guilds of London Institute in 1876, one of The Company’s most important acts supporting the field of technical education.

Photograph of Sir Sydney Waterlow

The Company first supports female education

In 1874, The Company made its first grants towards the secondary and higher education of women. A scholarship was first awarded in this year at North London Collegiate School and exhibitions, sponsored at Girton and Newnham Colleges, Cambridge, and Somerville College, Oxford. Grants were also made towards building costs; in 1880 alone, The Company contributed to a building fund at Newnham, paid for the construction of the Great Hall at North London Collegiate School and granted £500 towards the purchase of Watson House for Somerville College.

The Company also went further by paying for its former university scholars to take the ad eundem degrees offered by Trinity College, Dublin, in 1904; before this time, women could attend university and sit exams but were not permitted to graduate. The Clothworkers ‘much regretted that their scholars after creditable and sometimes brilliant work should quit these colleges without the titular academic stamps so much desired by the students’, wrote William Bousfield, Master, in The Times on 29 Dec 1904.

The Company’s involvement in secondary education was further expanded in 1894, when it became governor of the Mary Datchelor Girls’ School in Camberwell. The connection was to last until the school’s closure in 1981.

Stained glass window designed by Nathaniel Westlake for Mary Datchelor Girls’ School, Camberwell

The Royal Commission on Livery Companies

In the 19th century, the City of London livery companies were exposed to public scrutiny on a number of occasions as people increasingly questioned their role, privileges and wealth. In 1880, Gladstone’s government appointed a Royal Commission to undertake a complete appraisal of their constitutions, powers, modes of membership, entitlements, income (corporate and trust), estates and overall management.

The Clothworkers’ Company acquitted itself well under enquiry, although criticism was levelled against the vague nature of the Thwaytes’ Trust – ‘£20,000 to be laid out in the way that may tend to make the said Society comfortable’. The Commissioners noted that The Company spent a high proportion of its corporate income (in 1880, £20,000 of approximately £34,000 total) on voluntary charity, and did not claim the five per cent of income available for administration of their trusts. The Company was also cited for its work in promoting the establishment of Yorkshire College at Leeds and similar institutions in Bradford and Huddersfield.

The Commission concluded that the livery companies’ legal rights to hold corporate property not subject to any trusts were questionable, as was their ability to draw profit from the income and sale of these. It added that the companies could therefore be disendowed or disestablished by the State, although they did not advise this. Despite a number of recommendations, no practical action was taken by the Government, perhaps because the Commissioners disagreed over the nature of the reforms proposed. Commissioners Richard Assheton Cross (a Clothworker) and two others declined to sign the main Report (1884) and instead submitted a Dissent Report to Parliament condemning the proposed reforms, which would see companies ‘cease to be nurseries of charities and seminaries of good citizens’.

Despite the lack of consequent action on Government’s part, the Commission is believed to have galvanized many livery companies into adopting more proactive initiatives, renewing contact with their former trades and lending important support in the field of technical education.

Letter published in the Echo regarding reform of the City Livery Companies, 1881

Lord Kelvin becomes an Honorary Clothworker

Lord Kelvin, the 1st Baron Kelvin of Largs, was born William Thomson in Belfast in 1824. He was the son of James Thomson, a man of humble origins who rose to become Professor of Mathematics at the University of Glasgow.

An infant prodigy, Kelvin was educated at St Peter’s Cambridge where he subsequently became a Fellow, before accepting the Chair in Natural Philosophy in Glasgow at the age of 22. It was there that Kelvin undertook pioneering research into physics and the field of thermodynamics and developed the absolute scale of temperature, measured in units known as ‘kelvins’.

However, he is best known for his work on electricity and its application to submarine telegraphy. Kelvin was employed as Chief Engineer on the laying of the Atlantic Telegraph and was responsible for designing and making the instruments that ensured its final success, achieving a revolutionary signal speed of 14 words per minute.

Kelvin was knighted for this work in 1866 and received a peerage in 1892, the first scientist to be honoured in this way. He was presented with the Honorary Freedom and Livery of The Clothworkers’ Company in 1891, in recognition of his distinguished attainments. He became Master in 1900.

A testimonial portrait was commissioned by The Company from W.W. Ouless to mark Kelvin’s year of office. In return, he presented The Company with a fine silver-gilt steeple cup in 17th-century style. Upon his death in 1907, Lord Kelvin was buried in Westminster Abbey.

Portrait of Lord Kelvin by W.W. Ouless

The Company is presented with a new Master’s badge

The Company boasts one of the most splendid Master’s badges in the City of London, with a very interesting history. It was presented to The Company in 1905 by Frederick Morgan, Assistant.

The badge comprises gold, enamels and 16-carat diamonds in the form of The Company’s coat of arms. The large diamonds originally formed part of the crown worn by Queen Alexandra at her coronation in 1902. Alexandra’s husband, King Edward VII, was a Clothworker. At the time of her coronation, there were no female consorts’ crowns among the regalia (Queen Victoria having reigned for so long), and thus John Bodman Carrington was commissioned to design a crown, on the understanding that he would retain the jewels afterwards.

The Master’s badge was designed by Carrington, who was also married to a Clothworker Freewoman, and was intended to evoke the character of a 16th-century piece of jewellery.

The Master's badge

The Company celebrates its 400th anniversary

In 1928, The Company celebrated the quatercentenary (400th anniversary) of the granting of its first charter by King Henry VIII. To mark the occasion, Sir William Edgar Horne (Master, 1916) presented The Company with a magnificent standing cup and cover by Omar Ramsden, the noted Arts and Crafts goldsmith. The cup is art-nouveau in style and is The Company’s only solid-gold piece.

A celebratory dinner was also held on the occasion, 18 January 1928. Guests dined on a sumptuous feast of Whitstable oysters, poached fillet of sole d’Antin, sweetbreads à la princesse, saddle of Welsh lamb, roast pheasant with chips and salad, iced soufflé and herring’s roe with paprika. Sidney Neale Horne (who was to be Master in 1938) wrote in his menu card – retained in The Company’s Archive – that the champagne drunk that evening was one of the finest ever served.

Members of The Company were also presented with replicas of The Company’s historic 17th-century Chetwynd cups as an anniversary gift.

The Horne cup by Omar Ramsden, presented by Sir William Edgar Horne

Clothworkers’ Hall is destroyed

Clothworkers’ Hall was destroyed in a night of bombing and subsequent fires, 10-11 May 1941. The hall had already been hit in October 1940, but had escaped serious damage. The sustained bombardment known as the Blitz, between September 1940 and May 1941, caused huge damage to the City and East End, and to other parts of Britain. Many other livery halls were similarly destroyed as were several of The Company’s properties.

Fortunately, no-one was killed or seriously injured at Clothworkers’ Hall, although almost all the furniture and interiors were destroyed with the exception of a coat of arms, a small clock and four carved murals depicting the attributes of The Company – Loyalty, Integrity, Industry and Charity. The basement vaults – and consequently the Archives and some paintings – withstood the flames, although no-one dared open the strong room doors for a full five days after the fires were extinguished. The Company’s plate also survived, as many pieces were on loan in the US at the time and the remainder had been evacuated previously.

As the clear-up operation began, The Company took up business residence first at Christ’s Hospital, then at Great Tower Street, and later 48 Fenchurch Street (a Company property) and Company meetings and functions were held at Vintners’ Hall; The Grocers’, Fishmongers’, Ironmongers’ and Drapers’ Companies also lent their Halls on occasion. It was to be 17 years before The Company would return to (a newly built) Clothworkers’ Hall.

Photograph of the Master surveying the damage to Clothworkers' Hall

The sixth Clothworkers’ Hall is built

Plans to rebuild Clothworkers’ Hall were considered immediately after the War; however, it was many years until construction began, supervised first by Henry Tanner and later Herbert Austen Hall.

Herbert Austen Hall’s designs for the new livery hall took their inspiration from classical architecture; the marble-columned entrance hall is said to have been based upon one of the great temples of Persepolis. Due to financial exigency, his plans had to be repeatedly modified and a number of grander embellishments to the interiors were sacrificed.

What emerged was a new Clothworkers’ Hall ‘lightly clad in Georgian dress’ and in a style typical of much post-war construction in the City. In a break with the past, the new hall was approached through Dunster Court for the first time. Elements of continuity were evident in the design, in recognition of the Clothworkers’ centuries-long association with the site; the entrance gates of the Victorian hall were re-used and the reception room ceiling was modelled on the imposing barrel-vaulted plaster ceiling of its predecessor.

The Foundation stone was laid on 17 July 1956 by HRH Princess Marina, Duchess of Kent – 500 years since The Shearmen’s Company had first acquired the site – and was officially opened for business by Her Royal Highness Princess Mary, the Princess Royal, on 28 April 1958.

Photograph of H.R.H. The Duchess of Kent laying the foundation stone of Clothworkers' Hall, on 17 July 1956 [Getty Images]

The Company rationalises its property holdings

After World War II, The Company rationalised its property portfolio, selling off its suburban estates and purchasing plots in the City to form larger blocks ripe for later redevelopment, favoured by the City Corporation. The Company’s properties in Throgmorton Street and Copthall Alley, bequeathed by Thomas Ormeston in 1557, were supplemented with the acquisition of adjacent properties to form the Angel Court Estate. An ambitious development scheme was embarked upon in the 1970s to create 1 Angel Court, The Company’s largest office block in the City of London. The sale of the leasehold interest in this property enabled The Company to create an endowment for The Clothworkers’ Foundation in 1977, which today continues the long tradition of charitable giving on behalf of The Company.

Painting of 1 Angel Court under construction by Charlotte Halliday

The Clothworkers’ Foundation is established

In 1977, The Clothworkers’ Foundation was established as the independent charitable arm of The Clothworkers’ Company. The Foundation began making grants to charitable organisations in 1978 and has progressively assumed responsibility for the charitable work previously undertaken by The Company.

The Clothworkers’ Foundation is now among the largest grant-making bodies in Britain, and has since its establishment given away in excess of £140m to charitable causes. The Foundation aims to improve the lives of people and communities, particularly those that face disadvantage.

The Big House, which provides support and opportunities to young care leavers (2019 grant recipients)

The Lord Chancellor approves a new set of Ordinances

In 1984, The Company drew up a new set of Ordinances, the first since 1639, to remove those byelaws – in particular those relating to its original craft role – that had become antiquated in the modern age. Among other changes, the Ordinances placed female members on an equal footing with their male counterparts – removing the ambiguity of the ancient Charters and Ordinances over matters of gender – and enabled them to be promoted within The Company for the first time.

The Company's new coat of arms, designed by the College of Arms for the 1984 Ordinances

Clothworkers’ Hall is refurbished

When the sixth Clothworkers’ Hall was built, many of the intended embellishments had to be sacrificed due to financial constraints in the post-war era, and at first the rooms were rather stark and bare, although enlivened by gifts and antiques donated by members.

In 1985-1986, the interiors were refurbished by Donald Insall and Associates, in styles evoking the history of English Classicism from the period of Wren to the present, using materials and techniques intended to represent the best of British craftsmanship. Many of the Clothworkers’ heraldic motifs were also incorporated into the new furnishings in order to make the hall more personal to The Company, as its meeting place of several hundred years.

Painting by Alexander Cresswell of the refurbished Livery Hall

The Company elects its first Liverywomen

As a result of the changes instituted by the new Ordinances in 1984, The Company elected its first Liverywoman, Vanessa Woodbine Parish, in June 1994. She was swiftly followed by 13 more. A group portrait of the first 14 Liverywomen was commissioned to commemorate this historic occasion; it was painted by June Mendoza.

There are now several women on the Court of The Company, and, in 2017, we welcomed our first Lady Master, Dr Carolyn Boulter DL.

Portrait of the first fourteen Liverywomen by June Mendoza

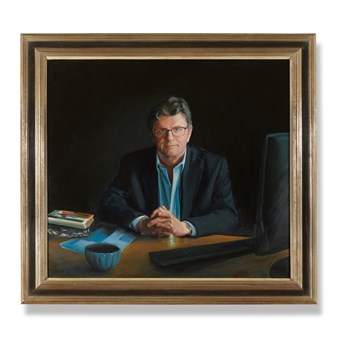

Appointment of Andrew Blessley as Clerk

After a successful career in banking (many livery company clerks hail from the military), Andrew Blessley was appointed Clerk in 2001 and tasked with streamlining and modernising The Company.

Changes and achievements during his clerkship include the rationalisation of a number of charitable trusts; the updating of all governing documents including the successful petition for a new and final Royal Charter in 2015; The Company embracing ‘trusteeship’ as it’s common purpose (given we no longer have a common trade to unite our members); the establishment of the Textile Sub-Committee to guide The Company’s strategy for textile support; and, significantly, the increasing professionalization of The Clothworkers’ Foundation with the introduction of regular policy reviews and rigorous assessment and monitoring processes to ensure it continues to be an impactful and focused grant maker going forward.

Blessley’s 14-year tenure placed The Company and The Foundation on a firm financial and administrative footing for our future as they near their 500th and 50th anniversaries, respectively.

Testimonial portrait of Andrew Blessley, by Paul Benney

The Foundation reaches the £100 million milestone

In 2012, The Clothworkers’ Foundation passed an important milestone: £100m in grants awarded since The Foundation was established 35 years before.

The Clothworkers’ Company had a centuries-long tradition of charitable giving, but it was not until 1977 that The Company created and endowed The Clothworkers’ Foundation as the primary vehicle for its grant making.

The Foundation now gives away in the region of £7m annually to charitable causes. Although the focus of and approach to its grant making has shifted over time, it nevertheless remains fundamentally committed to improving the lives of people and communities, particularly those facing disadvantage.

Royal Star and Garter was one of The Foundation’s grant recipients in this milestone year

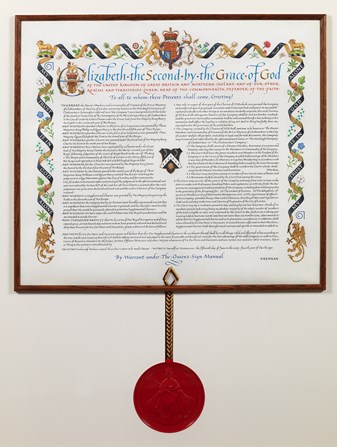

Supplemental Royal Charter granted by Queen Elizabeth II